GO TO OUR MAIN SITE 978.546.7620 EMAIL US

Michael McKinnell

1935–2020

-

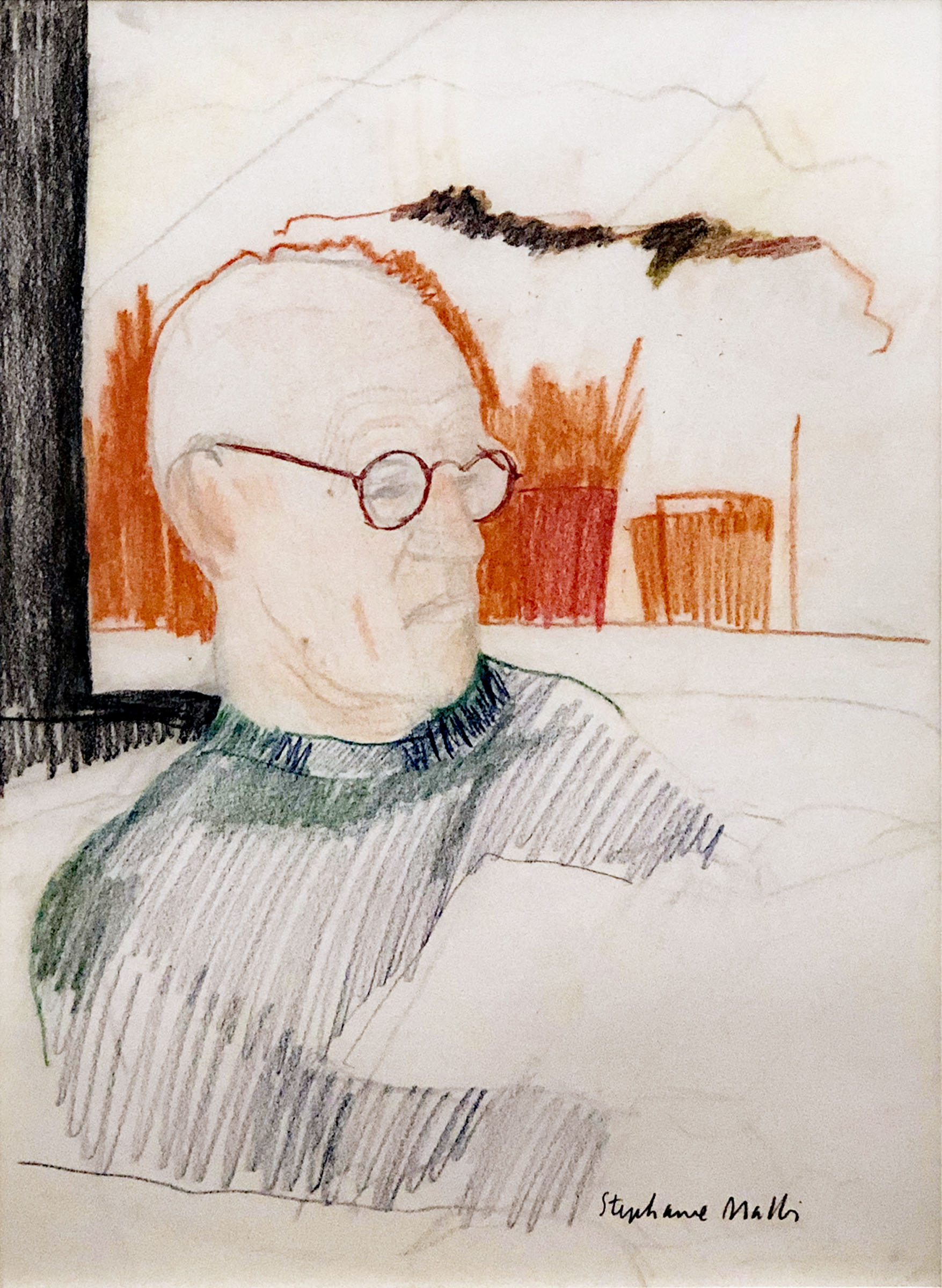

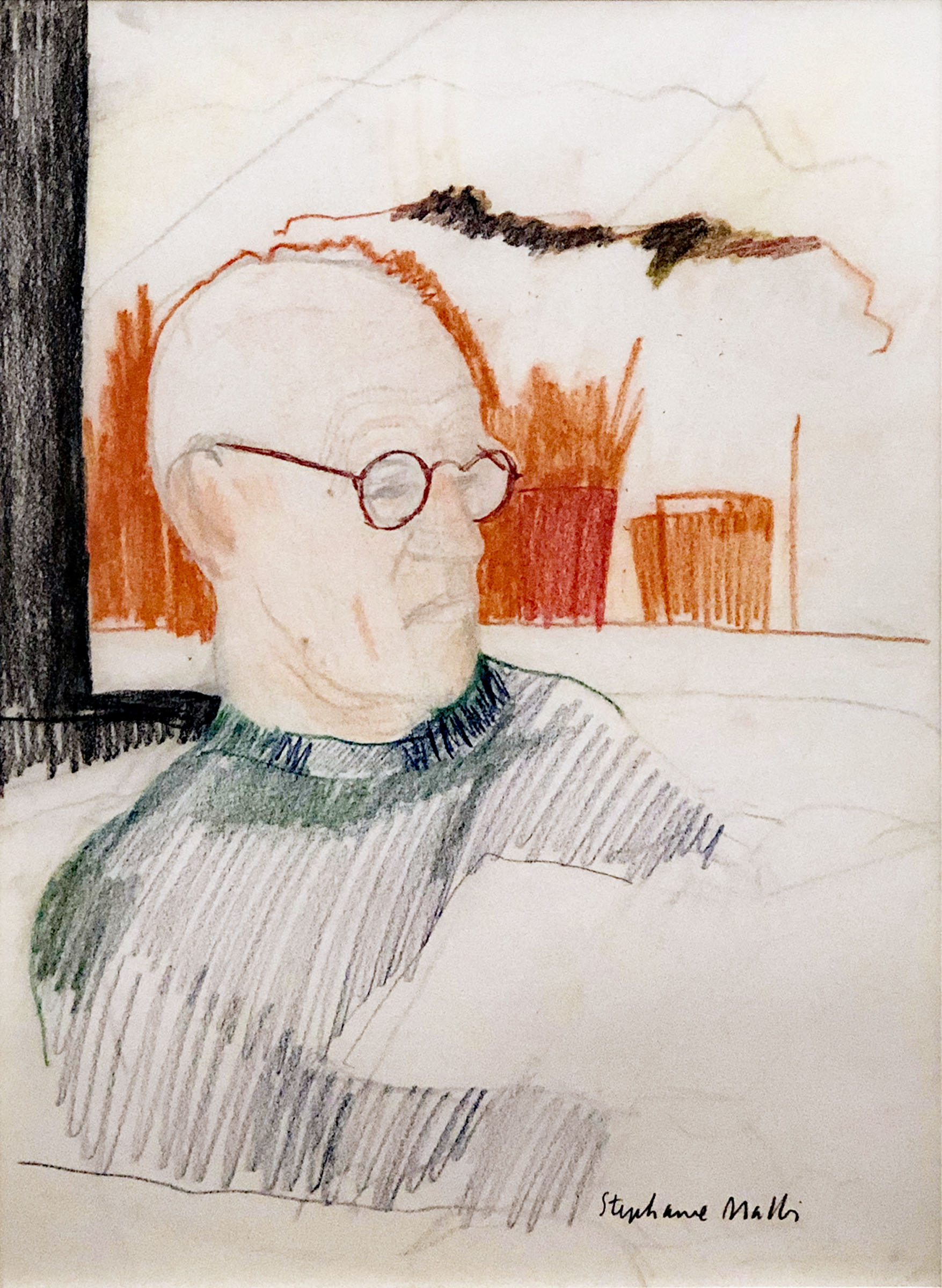

Michael Reading

Michael Reading

By Stephanie Mallis

9" x 12"

Pastel and graphite on paper image 1 of 15 -

slide 2 of 15

Inseparable

Works by Michael McKinnell

By Mark PasnikThroughout artist Michael McKinnell's body of paintings, we see the influences of masters like Braque, Picasso, and Bonnard in his exploration of composition and formal technique, use of color, celebration of pattern and geometry, and engagement with everyday subject matter. It is only with closer inspection that we see the influence of another important iconic voice, that of architect Michael McKinnell.

In many respects, the paintings McKinnell produced toward the end of his life are extensions of the artistry of his architecture. The lessons and preoccupations of his distinguished career as the creator of civic, institutional, and cultural buildings throughout the world make their way onto the canvas of his intimate look at his immediate surrounds in Rockport, Massachusetts.

The arc of his painting follows a similar pattern to the arc of his architecture career. McKinnell's early "quarry paintings" explored the massive granite deposits of New England's landscapes of extraction, not dissimilar from the monumentality of his concrete buildings from the 1960s and early 1970s — especially Boston City Hall (1969). The weight, the abstraction, the fascination with a robust material embracing space offer dramatic parallels.

Starting with the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1981), later buildings shifted away from abstraction and became more connected to place and history — and more delicate in their material qualities. Similarly, his still life paintings engage with snippets of domestic rooms enriched by patterns, geometries, and colors drawn from a humble setting. The newer paintings carry more direct and legible meanings. They are less heroic and bold, more astute and nuanced.

Continues

-

slide 3 of 15

Inseparable

Works by Michael McKinnell

By Mark PasnikParalleling his architectural process, McKinnell experimented with his medium across a sequence of paintings. The singular empty bottle, for instance, is explored as half shadow, half light on one canvas, abstracted to its essence. In another, the bottle's shadows and reflections are more ephemeral, smoke-like, and wispy. A third presents the bottle filled with wine, and a fourth shows the bottle as a refracted cubist-like figure.

McKinnell's still life paintings represent space frontally rather than literally. Instead of using strict perspective (in which lines recede to a vanishing point to mirror the way we see), his paintings are influenced by the architect's technique of orthographic projection (drawings such as plans and elevations that use parallel lines). Space is measurable and visually reconstructed following a logic not based on eyesight. A piece of fruit in the foreground and a teapot in the background are given the same scale and attention, the same immediacy.

By adopting techniques of architectural drawing into his paintings, McKinnell is engaging the architect's projective task — drawing something that does not yet exist — in contrast to the tradition of the still life painter's more direct observation of the existing world around him or her. While McKinnell's artworks record a subject matter that does, indeed, already exist, they imagine a new world projected onto the canvas. It is a world of vibrant color, tantalizing geometries, and intensified patterns, one as lovingly attuned to the value of materials as McKinnell was in any of his architectural projects. We witness the sheen of floor tiles, the fabric of wallpaper, the folds of tablecloths, the veining of stone, the grain of wood.

It is a world that is optimistic in its serenity and egalitarian in its attention to each element of the canvas. McKinnell's still life paintings, and his full life, are reminders that art and architecture, artist and architect, can be inseparable contributors to the simple act of reimagining our world.

Mark Pasnik is an architect and educator. He co-authored the book Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston and chairs the Boston Art Commission.

-

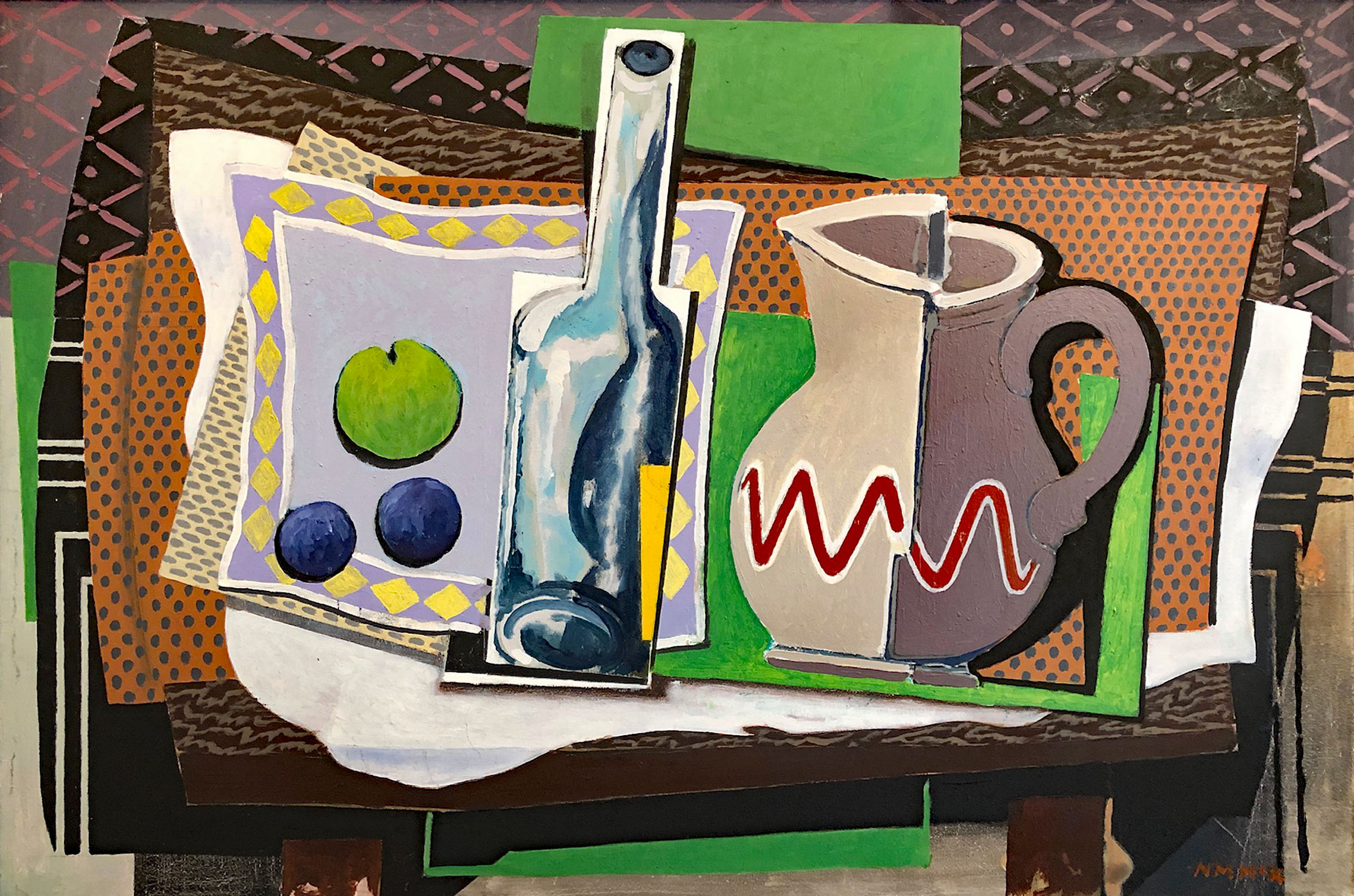

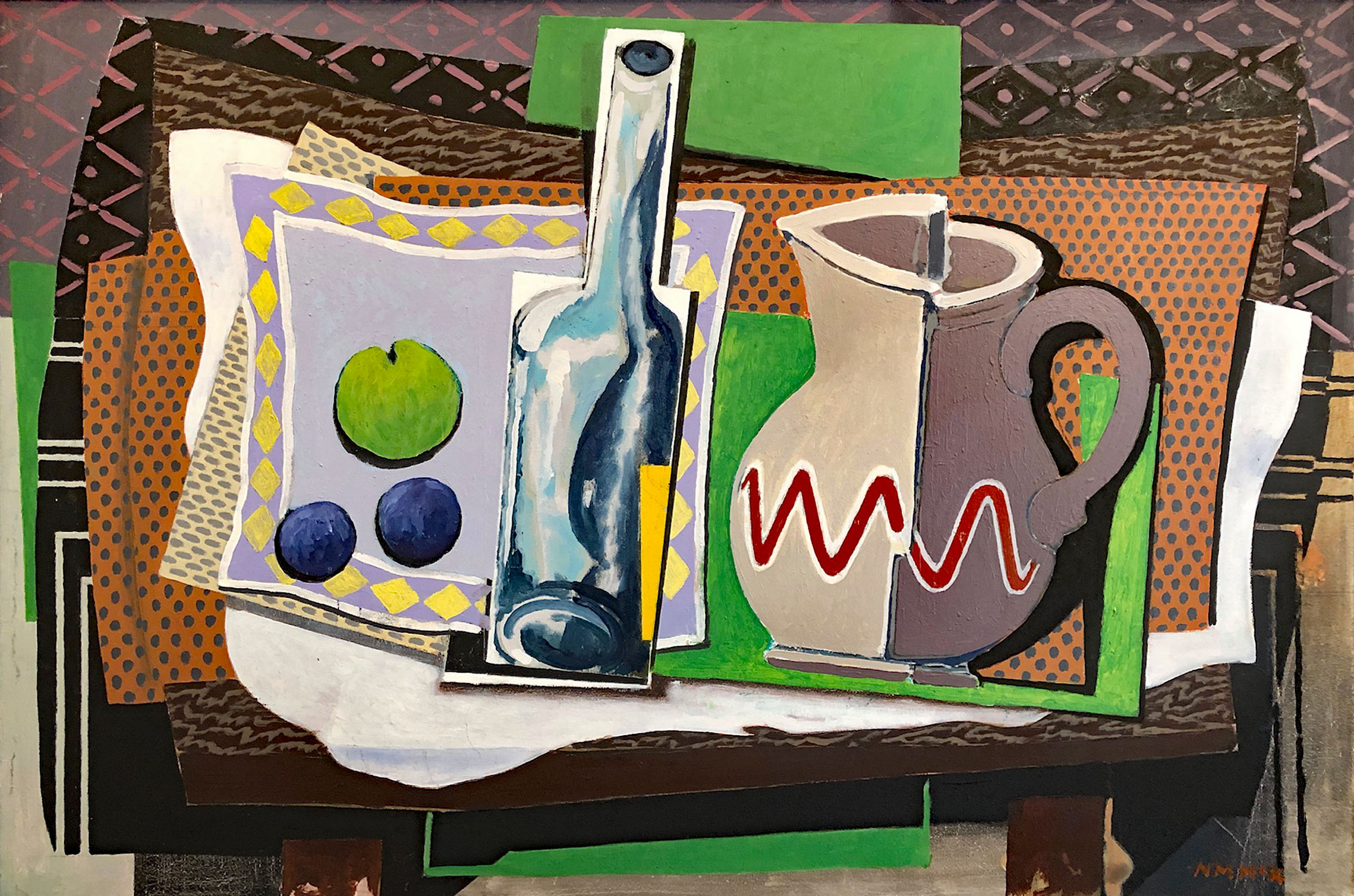

Still Life 1

Still Life 1

24" x 36"

Oil on canvas slide 4 of 15 -

Still Life 2

Still Life 2

24" x 36"

Oil on canvas slide 5 of 15 -

Still Life 3

Still Life 3

48" x 24"

Oil on canvas slide 6 of 15 -

Still Life 4

Still Life 4

24" x 48"

Oil on board slide 7 of 15 -

Still Life 5

Still Life 5

48" x 24"

Oil on board slide 8 of 15 -

Still Life 6

Still Life 6

36" x 24"

Oil on canvas slide 9 of 15 -

Still Life 7

Still Life 7

36" x 24"

Oil on canvas image 10 of 15 -

Still Life 8

Still Life 8

24" x 36"

Oil on canvas slide 11 of 15 -

Still Life 9

Still Life 9

42" x 30"

Oil on board slide 12 of15 -

Still Life 10

Still Life 10

30" x 36"

Oil on board slide 13 of 15 -

Micheal

Micheal

By Stephanie Mallis

8.5" x 11"

Pastel on paper slide 14 of 15 - slide 15 of 15

-

Michael ReadingBy Stephanie Mallis9" x 12"Pastel and graphite on paper

image 1 of 15

Michael ReadingBy Stephanie Mallis9" x 12"Pastel and graphite on paper

image 1 of 15

- slide 15 of 15

-

Still Life 124" x 36"Oil on canvas

slide 4 of 15

Still Life 124" x 36"Oil on canvas

slide 4 of 15

-

Still Life 224" x 36"Oil on canvas

slide 5 of 15

Still Life 224" x 36"Oil on canvas

slide 5 of 15

-

Still Life 348" x 24"Oil on canvas

slide 6 of 15

Still Life 348" x 24"Oil on canvas

slide 6 of 15

-

Still Life 424" x 48"Oil on board

slide 7 of 15

Still Life 424" x 48"Oil on board

slide 7 of 15

-

Still Life 548" x 24"Oil on board

slide 8 of 15

Still Life 548" x 24"Oil on board

slide 8 of 15

-

Still Life 636" x 24"Oil on canvas

slide 9 of 15

Still Life 636" x 24"Oil on canvas

slide 9 of 15

-

Still Life 736" x 24"Oil on canvas

image 10 of 15

Still Life 736" x 24"Oil on canvas

image 10 of 15

-

Still Life 824" x 36"Oil on canvas

slide 11 of 15

Still Life 824" x 36"Oil on canvas

slide 11 of 15

-

Still Life 942" x 30"Oil on board

slide 12 of15

Still Life 942" x 30"Oil on board

slide 12 of15

-

Still Life 1030" x 36"Oil on board

slide 13 of 15

Still Life 1030" x 36"Oil on board

slide 13 of 15

-

MichealBy Stephanie Mallis8.5" x 11"Pastel on paper

slide 14 of 15

MichealBy Stephanie Mallis8.5" x 11"Pastel on paper

slide 14 of 15

- slide 15 of 15

<

>